Bodhisattva Miquella - Elden Ring Cosmology Theory

Exploring Buddhist themes in Elden Ring's cosmology and the light they shed on interpretations of Miquella.

An essay inspired by Talvasha’s reddit post [1] identifying many of the main themes linking Miquella and Buddhism. Below is an intro to their findings along with additonal details found through my research.

Groundwork

For the purpose of this discussion, I have referred to East Asian (Japan, China, Korea) Buddhist traditions. There are many interpretations and some beliefs that overlap Hinduism, but this is a Japanese game, so I default to their traditions foremost.

In the most basic sense, karma (Sanskrit for ‘act’) can be understood as every action one takes giving rise (or ‘ripening’) to consequences or effects. [2] The effects can be good or bad, and ripening can happen in the current life, a future life, or be happening at present from a past life. Freeing oneself of bad karma entirely is a key step of breaking the cycle of rebirth and attaining enlightenment.

It is interesting to note that the cycle is often depicted in Buddhism with the eight-spoked wheel of dharma; an ancient Indian symbol that has also been used in connection with worship of the sun. While intriguingly similar to Fell God symbolism, this is not relevant to the discussion at hand.

Enlightenment; The Act of Awakening

Achievement of enlightenment in Buddhism is called Bodhi, which has a root meaning of “awakening”, an interesting contrast to Trina’s power of sleep. Another term used is Vimukti, which is freedom from hindrances and a state of “non-attachment, non-discrimination and non-duality”. [3] This reveals a key misunderstanding many have had regarding Miquella’s divestments.

The process of ascending to this state is abandoning the “fetters” or ties binding one to the cycle of rebirth. The goal is rejection of the material world, of which there couldn’t be a more obvious example than discarding the material body itself.

One must abandon both the desire for pleasure and aversion to pain, and remove both gladness and discontent. [4] Miquella’s abandonment of his love - 愛 - is used to mean both love and affection, but also attachment and desire in Buddhism. [5] Leda says Trina’s love for Miquella is “boundless”, but this is love for Miquella. For his well-being, his joy, his inherent “self”. Everything he must abandon.

Bodhisattva of Compassion

In Buddhist tradition some beings are able to achieve enlightenment but choose willingly to remain an individual entity to assist others. They are called Bodhisattvas, motivated by a “need to replace others' suffering with bliss”. [6] They are roughly the equivalent of Catholic saints, being devoted to saving the suffering beings in this world. Despite having shed their “love” or emotional desires, they are still capable of limitless compassion.

One notable Bodhisattva was the Indian prince Avalokiteśvara, a key figure of the Lotus Sutra [7], who had the “desire and ability to help all without distinction.” [8] We know this was a goal of Miquella’s too:

Light of Miquella : “Miquella sought to accept all that was and would be”

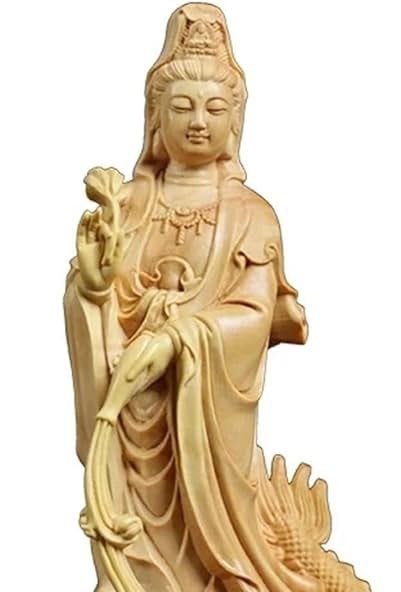

Avalokiteśvara was the primary bodhisattva of compassion, and a popular deity when Buddhism spread to China, and during the Tang dynasty (600~900 AD) began being depicted in a more feminine manner. By the Yuan dynasty (1271~1368 AD) had taken a feminine form and surpassed even his role in Buddhism to become Guanyin, the Chinese Goddess of Mercy and Compassion, who is known in Japan as Kannon. [9]

Two of Guanyin-Kannon’s iconographies are a willow branch, used “to sprinkle the dew of compassion on all beings, relieving their suffering” and a vase of nectar which grants “spiritual nourishment and healing”. [10] These are very compelling parallel to the Bewitching and Charming branches used by Miquella and Trina’s followers, as well as the cut content of Trina’s “dreambrew”, which was intended to let the player collect dreams. It’s also reflected in the nectar we can imbibe from Trina’s corpse-flower to fall into velvet sleep and commune with her.

The syncretism of Guanyin and Kannon has extended even further into representation as the Virgin Mary, reinforcing the universal appeal of this deity. In the Edo period, Japanese Christians would disguise statues of the virgin Mary as Guanyin, and this syncretism sometimes appears even in the modern day. In this form, the gendered dualism remains and can be understood as representing both Jesus and Mary in the role of a god bringing mercy to the world. [11]

It isn’t hard to see a clear connection between a dual-gendered bodhisattva of compassion and Miquella, a dual-gendered god of compassion.

Golden Circlet of Supression

In the Chinese epic Journey to the West, the character of monkey king Sun Wukong is symbolic of the unruly nature of man. He is tricked into wearing a circlet gifted by Guanyin that subdues his aggression and rebelliousness by inflicting pain when he does wrong. Once Sun attains Buddhahood, the headband vanishes.

Circlets of the same origin appear in Chinese opera to depict martial monks that have taken a vow of abstinence. They are called Jiegu (戒箍), a “ring to forget desires”. [12]

Miquella’s ability to suppress the aggression and cause forgetfulness of impossible desires in his followers are a direct analogy of these circlets. And of course, it is the circlet symbol that we ourselves see while we are being charmed during the fight, reinforcing this connection.

Wrathful Guardians

Another type of bodhisattva or divine being which exists in Buddhism are Dharmapalas. These deities are depicted as fierce or wrathful due to “their willingness to defend and guard Buddhist followers from dangers and enemies.” [13]

One of the dharmapalas of Avalokitesvara is Skanda/Wei Tuo [14], a Chinese general who met the bodhisattva while he was incarnated as a princess. Skanda likely originates from Kartikeya, the Hindu god of war, who played in the cosmos and “fiddled with the orbits of planets” as a child, and bizarrely rides a peacock. [15]

In Cosmology Theory, Miquella is linked to war through the symbolism of the male pillar, which contains wisdom, love and conquest. [16] The existance of Guanyin’s dharmapala as a war-centered diety is another key explaining why a god of compassion is presented with an extremely battle-oriented companion.

Age of Compassion

With the symbolic links above, what can we say about the purpose and function of Miquella’s Age of Compassion?

Some see it as a stagnant age where no-one is able to suffer, but all are constrained and thus personal growth and the conflict of competition both are stifled. This is a valid interpretation of the result, but is unlikely to be the intent.

Remember what was said about karma at the start of this essay. Freeing oneself of bad karma entirely is a key step of breaking the cycle of rebirth and attaining enlightenment. By using a symbolic Jiegu to subdue people’s aggression and the “willow branch” of Kannon to cause forgetfulness of desires, Miquella prevents people from commiting the type of acts which accumulate bad karma.

Despite this, he does not prevent the existing negative consequences of acts, as we see he doesn’t attempt to repair harms such as the abandonment of the Kindred of Rot by Malenia or Hornsent’s hatred for Messmer. These consequences exist in the world and must be worked through. But over time, when no further evil is done, only “good consequences” would accumulate.

Like all ages, eventually Miquella’s would come to an end, and probably in a state of decay and disillusion like all others. It would leave people abruptly bereft of a love and peace they had known their whole lives, and little understanding of how to deal with the evils of each others - and their own - true desires.

But it would also give the world a lengthy repreive from suffering. It would create harmonious societies and prove the possibility of all creatures and beliefs existing and working together. It would generate “good consequences” for people and the world as a whole, a knowledge of peace to draw upon in coming troubles. This is an inversion to Ranni’s age which would provide freedom to experiment, to disagree and debate, to air skepticism and choose ones own path. It too, would end, but would exist in memory and culture as an possibility for the next age.

Miquella and Ranni, working at exactly cross purposes but both for a greater ideal, wish to “reset” the existing system. I don’t believe either intends to be “eternal” or break the cycle. The cycle of life cannot be broken, and this was Marika’s failure. Both of these new gods aim ultimately to gift the world new tools, new modes of thought and ways of living to use in the endless rhythm of life progressing forward.